The goal of The New York Times Simulator, a new, free game, is simple: keep readers happy and don’t get shut down. It’s a problem any modern media outlet knows well. But this new game doesn’t just make you any old journalist struggling to make a living in today’s fraught media landscape. No, it puts you in the shoes of the paper of record’s editor-in-chief. It’s a game about navigating the mission of publishing “all the news that’s fit to print” when your key demographic may not want to hear that news, or may want it softened or ideologically slanted for their comfort. It’s a radical work of games as satire that shines a light on the power of editorial angle and influence, illuminating just how important word choice can be in influencing public perception.

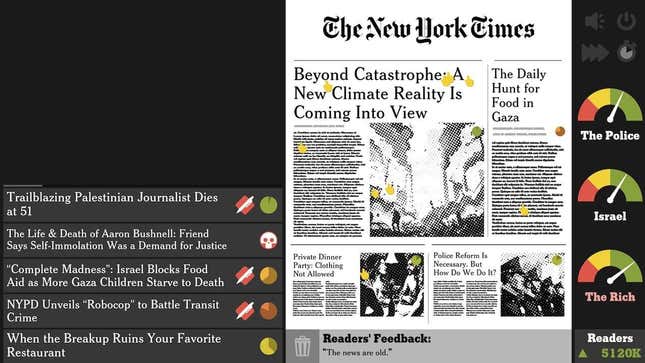

The game, from developer Molleindustria, has a simple structure with only a few tasks you need to keep track of, and sessions only last roughly ten minutes. Stories will cue up on the left side of the screen, some of which allow you to edit the headline and frame the story in a different way. These stories must then be placed on the front page, either above or below the fold, and placement will give more or less importance to a story and how readers react to it. Finally, a count of readership is shown, as well as meters keeping track of how the paper’s three key demographics are reacting to how the news is being presented. The New York Times Simulator identifies those key demographics as the police, Israel, and the rich. Very quickly you learn how these demographics will react to stories, and it’s up to you to react accordingly.

Headlines like “The Palestine Double Standard” or “After Curfew, Protesters Are Again Met With Strong Police Response” roll by at breakneck speed. Unlike Lucas Pope’s The Republia Times, which this game uses as inspiration, The New York Times Simulator plays out in real time to reflect the 24-hour news cycle. And while at first you may be preoccupied with frantically rushing to place stories with optimal headlines in optimal positions on the paper, as you get used to the flow of the game, something quickly becomes clear: Most of these headlines are real.

They’re literally ripped from the headlines of some of the biggest publications in the world, including, of course, The New York Times. But some stories have multiple headline options, and even those are often based on real edits that stories have received. (An extensive list of the game’s headlines, alternate headlines, and the stories they are taken from can be found here). What becomes clear as you place enough stories and change enough headlines is that the story that ran in real life is typically the one that obfuscates the story in benefit of appealing to the paper’s key demographics. It foregrounds this problem by shedding a light specifically on how rampant this issue is in real newspapers such as The New York Times.

While The Republia Times was a commentary on censorship, The New York Times Simulator replaces that with a focus on the propaganda model of media. As described by Edward S. Herman and Noam Chomsky, the propaganda model asserts that “the mass media serve as a system for communicating messages and symbols to the general populace,” and that “in a world of concentrated wealth and major conflicts of class interest, to fulfill this role requires systematic propaganda.” This is explicitly what Molleindustria wants players to take away from this game, as stated in the game’s release notes.

By actively training you on how to best appease biased readerships in order to keep the paper afloat, The New York Times Simulator is also asking you to recognize these patterns in life. Things like passive voice and biased euphemisms are constantly on display. By reducing the news to headlines on a single front page, The New York Times Simulator reflects the reality of modern, mainstream news readership. Most people only read a headline, be it on the front page of a paper’s website or in passing on a social media post.

Headlines shape how most people think about and engage with the news, so the choice of just a few words is vital to determining how people frame a story in their minds. Playing The New York Times Simulator, I was reminded of a conversation with artist Alexandra Bell I attended in journalism school. Bell, a graduate of the Columbia Journalism School, discussed her art series “Counternarratives,” which presented large-scale versions of real New York Times pages that Bell had edited to highlight the inherent biases embedded in the news media and challenge the idea of objectivity.

The New York Times Simulator is hitting on the same themes. As a piece of art meant to radicalize players against a systemic issue in society, it gives them the power to stop being passive themselves and take action. It is entirely within the player’s power to determine what news is fit to print and how to present it.

The game never tells you that you need to follow the unspoken rules of the paper. You can print headlines that bravely confront news topics head-on in ways that some readers may find alienating, placing those stories on the front page to better serve the reader by presenting the news they need to know. This might drive readership down and anger your key demographics, but that isn’t necessarily a bad thing. Maybe The New York Times should be driven into the ground…in the game.