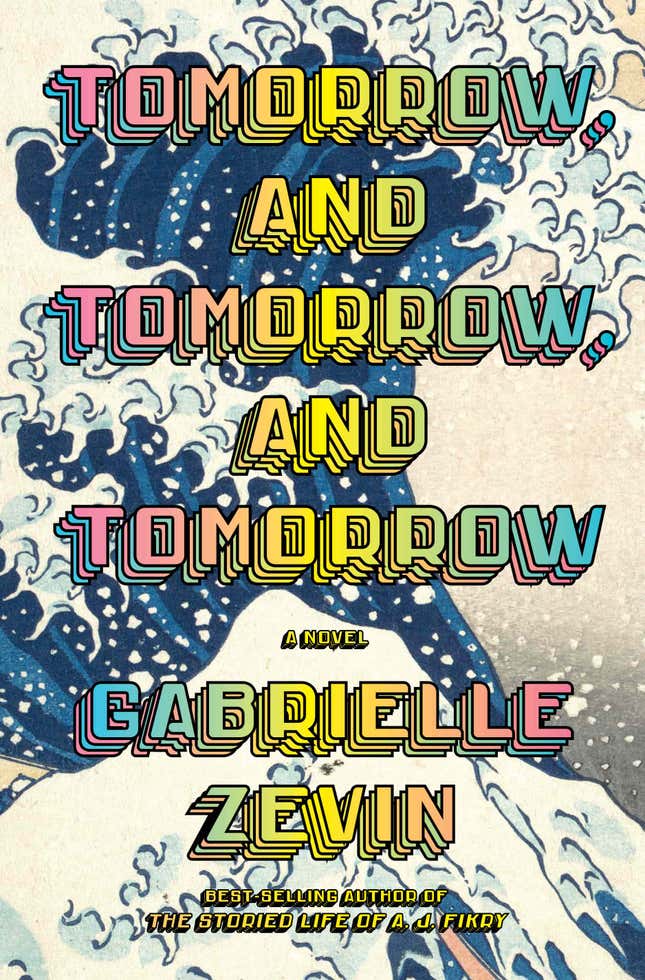

We will never find the Fountain of Youth people fantasized about centuries ago, but, out of our woe, we can make games. Games let you live again and again in eternally perfect, preternaturally strong bodies, and for the friends in novelist Gabrielle Zevin’s latest book Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, this is more than enough.

A “game,” to them—and to Zevin—is everything. From the 80’s to early 2010’s, Sam (mother died in a car accident, Harvard math dropout, good in front of crowds), Sadie (doesn’t believe in marriage, MIT game design wunderkind, prone to working crunch hours), and, for a time, Marx (rich, handsome, Harvard-roommate-turned-game-producer) come together because of games. To them, playtime is personal, political, and the result of their dedicated, exacting work. Games require blood sacrifice—not sleeping enough, fighting too much—but in them, you can claim your little piece of immortality.

Sam, whose leg was shattered in 27 places in the devastating car crash that killed his mother, turns to games to inhabit a body more steady than his own. Sadie, who got into games while her sister battled childhood cancer, likes losing herself in a better, safer world. And Marx just thinks games are fun.

But Zevin maps their disparate reasons for playing to their temperaments. At Unfair Games, the company conceived in their college apartment, Sam is fond of creating in-game facsimiles of himself, Sadie rages over the real world’s blindness to women developers, and Marx, again, likes having fun.

To these characters, video games are a necessity indistinguishable from all of life’s other worthy pursuits, on par with or better than making lots of money and having sex. Zevin presents their devotion to the craft with gentle authority. By the end of my reading, some of which I spent a bit weepily, thinking about the friendships and games in my life, I felt that my belief in video games had been restored. I didn’t even know it needed restoration. But Zevin suggests that games are like relationships, in that way. They are things that could tap you on the shoulder when you’re busy being brooding and occupied, reminding you that everything and everyone occasionally requires some TLC.

Tomorrow’s third-person omniscient narrator, whose storytelling flits across decades (“[Sadie] would never be much of a drinker,” the narrator informs us while Sadie is still in college), and in one particularly meta section, dives into a game, pronounces aphorisms about the overlap of play, life, and love like a Greek oracle in reverie.

“To play requires trust and love,” “A name is destiny, if you think it is,” “the human brain is every bit as closed a system as a Mac,” it predicts with delicious conviction. The title Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow on its own is a sort of bold divination, coming from a soliloquy in Marx’s beloved Macbeth. In the address, Macbeth dismisses life as “a tale / Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, / Signifying nothing.”

“What is a game?” Marx asks Sam and Sadie. “It’s[...]the possibility of infinite rebirth, infinite redemption. The idea that if you keep playing, you could win.”

Though Marx and Sadie’s friendship eventually turns romantic, Sam and Sadie, the older, arguably, more important relationship (“There were so many people who could be your lover,” the narrator says, “but[...]there were relatively few people who could move you creatively”) never does. It, instead, alights and broils for three decades. They come together, pull apart, come together, pull apart. It’s not romantic, Sam and Sadie themselves say often, but it is devotion. Like trying to reach a high score or believing in a God. “He has made everything beautiful in its time,” says Ecclesiastes 3:11. “He has also set eternity in the human heart.”

Despite its everlasting chastity, Sam and Sadie’s relationship reminded me of the time-spanning romances in the movies The Way We Were and When Harry Met Sally…, both of which, like Tomorrow, are more interested in the process of love than the kissing. Friendship is a form of art, a prayer. But, memorably, in The Way We Were, Barbra Streisand’s character pleads with Robert Redford, who is on the brink of leaving her and becoming nothing more than a friend.

“Couldn’t we both win?” she asks him sincerely.

No, we couldn’t. In Sadie’s childhood favorite game, The Oregon Trail, hunting more bison than you can eat allows their meat to spoil. For you to live in sensual excess, the bison must lose—Sadie feels bad about this. Sam, Sadie, and Marx all love each other from their heads to their toes, but when Sadie and Marx fall in love and buy a house, Sam feels that he’s some platonic love loser. Everyone wants to win. Everyone wants more. But Zevin finds comfort in everyday losses—in business, love, and death. Like Marx (and Shakespeare) says, despite any diminishing returns, humans don’t give up, we wait for something good to float down into our palms.

Zevin spends much of the novel ruminating on this contradiction. In games and in getting older, interpersonal drama and death become expected. Cheap. Still, you hold tight to the moments that lit you up, a week ago, ten years ago. Another game designer, at one point, tells Sam that she loves the way Sadie “does blood.”

“Maybe it’s my imagination,” she says, “but I feel like she has people bleeding slightly different colors[...]. It’s a small thing, [...]but I’m obsessed with it.”

Likewise, Sadie’s anger with Sam always softens when she recognizes him as the child she met in her sister’s children’s hospital decades ago, or as the boy she ran into again at college, who lied about being able to see the hidden image in the Magic Eye posters that beguiled the 90s.

“This is what time travel is,” Sam thinks to himself during that college run-in. “It’s looking at a person, and seeing them in the present and the past, concurrently.”

The only thing that gifts you immortality, apart from video games, Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow suggests, is hope. That “thing with feathers,” Emily Dickinson wrote once. “That perches in the soul - / And sings the tune without the words - / And never stops - at all -.”

The book is buoyant despite the illness and pain that speckles its characters’ lives because they hope to meet again, to play again, to build again like gods. Even nasty Kotaku commenters, who Zevin amusingly notes responded to Sam saying in an interview that “there is no more intimate act than play, even sex” with deciding “there must be something seriously wrong with Sam,” cannot tamper the internal motor that makes us want to live, again, again. This book, with its respect for craft—the craft of love and games, or loving games—will remind you of how abundant one life is, how lucky we are to keep each other in our memories forever.