I’m not interested in just vaguely gesturing at what Slay the Princess, a horror, time-loop visual novel from Black Tabby Games, is actually about. Often there’s an assumption that a review will be a spoiler-free assessment of whether or not something is worth your time, keeping its distance and speaking in broad generalities. But sometimes, you need to engage with what a work is really doing in order to say anything meaningful about it, and I don’t think talking around the specifics of Slay the Princess will do it justice. Anyway, I pretty much already did that already when I previewed the game earlier this year. So if you want to know if you should play Slay the Princess, the answer is yes. If you want to know why, read on.

Slay the Princess appears pretty single-minded in the beginning. You’re thrust into a situation with no context, walking through a forest toward a cabin where a princess who allegedly will destroy the world is being kept at bay by a single chain around her wrist. It’s up to you to slay her and save everyone. You’re told all this by a narrator who refuses to elaborate on some of the most basic information. How is she going to destroy the world? Does she even want to? Does her apparent capability to destroy the world mean she must die?

All of these questions spin through my head as I enter the cabin. There’s a knife sitting on a table, but little else hints at my grim task until I descend the stairs and find the princess chained up. I had already tried to talk to her in the original demo, so I thought I’d shake up my strategy this time and not entertain having a conversation at all. Instead, I walked right up to her, used the blade I’d picked up on the way in, and stabbed her without hesitation. Then I made the mistake of removing the blade, and she stabbed me with her own weapon. As we both bled out on the floor of the dungeon, we were caught in the loop of our creator’s design.

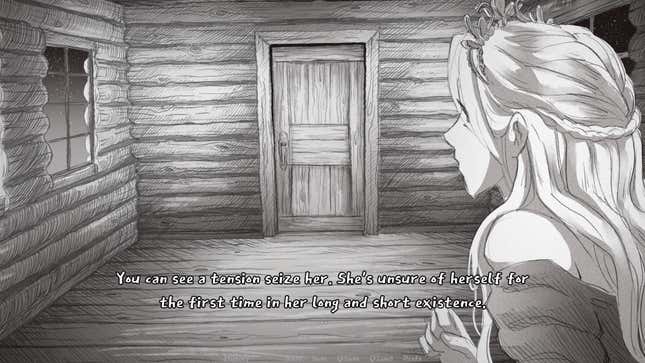

I wake up back outside the cabin, with the narrator once again telling me I must slay the princess and save the world. Every question I ask about the apparent loop I’m in sparks more confusion between me, the narrator, and the literal voices in my head. But nevertheless, I head back into the cabin and find it’s not quite as I remember it. There’s a mirror on the wall that disappears when I try to look into it, the stairwell isn’t quite as I remember it, and the princess has evolved into a monstrous version of herself. This loop repeats itself, with the princess appearing in different, terrifying forms each time, until the princess and I find ourselves in a strange pocket dimension between the loops, able to talk without the narrator there to tell us what to do.

In this in-between space, Slay the Princess gets existential. The princess is essentially absorbing each variation of her we meet in these time loops to find new understanding. Each possibility is a different version of who she could be based on the slightest alterations to how I reach her in the dungeon. She acknowledges that each version of her is her, but by experiencing all these realities, she is able to gain a greater understanding of who she is and who she can be. She grows beyond what the narrator has told her she is, but acknowledges that certain parts of her are inherent, and others are determined by what happens to her in a loop.

She asks that I continue to go through the loop to bring her new perspectives, and so I do it. I pick different dialogue options that determine which version of the princess I’ll find in the dungeon, and by the end, I’d brought her so many variants that she had transcended the understanding the narrator had spouted off at the beginning of each cycle. Even if I wasn’t mesmerized by the existentialism and stellar prose of Black Tabby Games’ writing, the reveal of what kind of horrific monstrosity the princess would appear as on each loop was motivation enough to keep running down the stairs into the dungeon again and again.

Sometimes the princess would just appear as a very tall version of herself towering over me, while at others she would be a vicious, blade-bearing terror. There was even a time when she’d taken the form of animals, circling around me in the darkness as if I were her prey. Sometimes I slayed her, other times she slayed me. Eventually, however, as her understanding grew, the narrator’s control over the situation shattered– literally, as the mirror that kept appearing between loops broke, showing pieces of this previously unseen figure’s appearance in its cracked shards. Though the image is broken, I’m able to see that the narrator is bird-like, and is apparently responsible for the creation of the princess, who is meant to embody destruction, death, and the rebirth that comes after.

The narrator fears death, and thus wants to create an entity that embodies it and can be destroyed, but that entity also takes the form of whatever anyone perceives her to be. If death is a frightening, debilitating concept to you, the princess becomes a monster. If you approach it without fear, she will appear as an approachable human being. Thus the multiversal cycle we find ourselves in now. The simulation the narrator has put us in means we can follow every permutation to its natural conclusion, but now that the princess is aware of what she is, there’s a new conundrum. If she is allowed to exist as the god of destruction she was designed to be, she can escape this construct and lay waste to the outside world.

With the mirror that embodied him broken, the narrator is not long for this world, and you interrogating him in his final moments makes for Slay the Princess’ most memorable scene. As you ask each question, pieces of the mirror you’re looking at disappear, taking the narrator with it. I quickly realize I have more dialogue options than pieces of the mirror, and the stakes of each question I choose to ask grow much higher. There’s no time to get too inquisitive, as I only have a limited amount of time with the game’s info dump. But as I talk to him, it becomes very clear the narrator has a specific vision of who the princess is, and who I should be. He spends the entire conversation warning me about the dangers of an entity he created that has long been shaped by others’ perceptions of her. As far as he’s concerned, her existence, the threat of death and destruction, is what keeps people from being without fear. Is her life worth a burdenless existence for the rest of the world?

I can ask all the questions I want, but in the end, it will just be me and the princess here to decide what’s next. She has ascended to godhood, and I can either leave this simulation with her as gods and play out what the narrator feared, or you can rewind the entire scenario, and talk to each other as a princess in a dungeon and her would-be assassin and choose to leave it as people, rather than gods.

There’s a lot of minutiae in the space between Slay the Princess’ multiple endings, but while much of the conversation around Black Tabby Games’ visual novel is around the various, monstrous forms the princess takes in each loop, all I can think about is this final cycle. Whichever sequences of events you choose to follow, it’s here that you and the princess finally see each other for what you actually are. This is both as gods meant to embody ideas, but also as people, long-beholden to the views of your creator, and the hypothetical threats you pose to the people outside this construct.

Slay the Princess is all about time loops, mind-bending twists, and terrifying character design, but at its center, it is about being seen for who you really are, rather than what can be summed up in a second-hand account of what you’re perceived to be. The first time I played through the ending, I chose to have the princess and I leave the construct as gods, believing death was part of the human experience that makes life worth living. But after replaying it, I chose to find the princess in her chains once again, and to free her from the cycle entirely, leaving as ourselves.

This world we live in is so often depersonalizing, feeling dismissive of everything we individually want and believe ourselves to be, as we’re so often in the vice grip of what others want or believe us to be. Our employers try to quantify our usefulness on spreadsheets and we seek validation from strangers to tell ourselves we are worthy of love, all of which contribute to a distorted and potentially false reflection of who we are, what we believe, and our own self-worth. The way others view us defines our day-to-day, but only if we let it.

In following Slay the Princess to this conclusion, I’m overcome with an oppressive, weighty lethargy. It should be so cathartic to play a game where you can remove yourself from a cycle like this, but it only makes me wish it felt possible to be so clearly understood and free from the shackles of others’ visions of who you are in the real world. Slay the Princess instills hope in me that such freedom exists and despair at just how tired I am in equal measure. But at least it makes me believe in possibilities, even if they might take a few loops to see to the end.